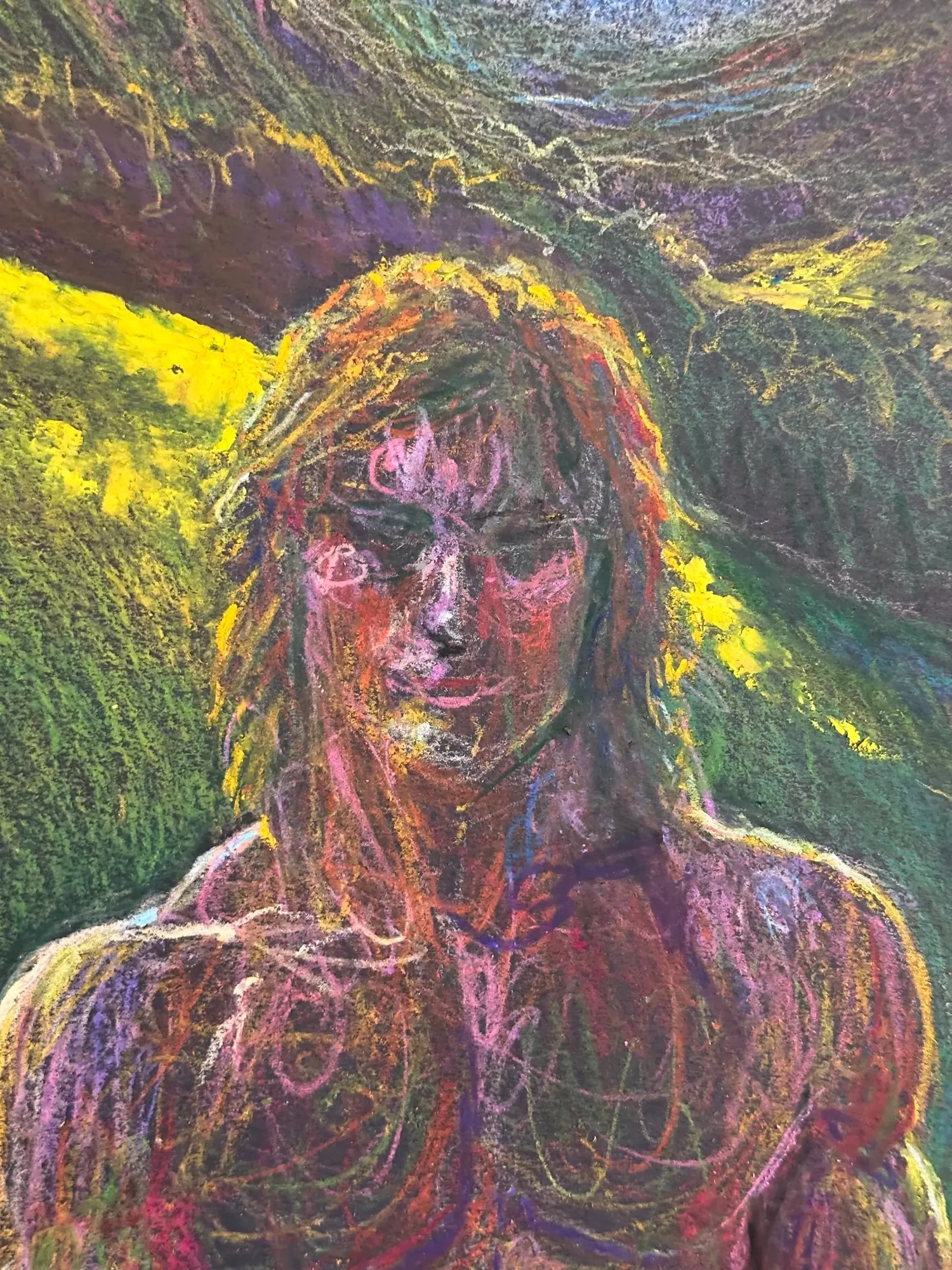

Keeper of The Valley turns a classical format—front-facing figure in landscape—into something rougher and more immediate. The nude man stands centered, shoulders squared, gaze forward. He holds a thick bouquet low across his body, the stems and blooms covering the pelvis while also behaving like a tool or harvest.

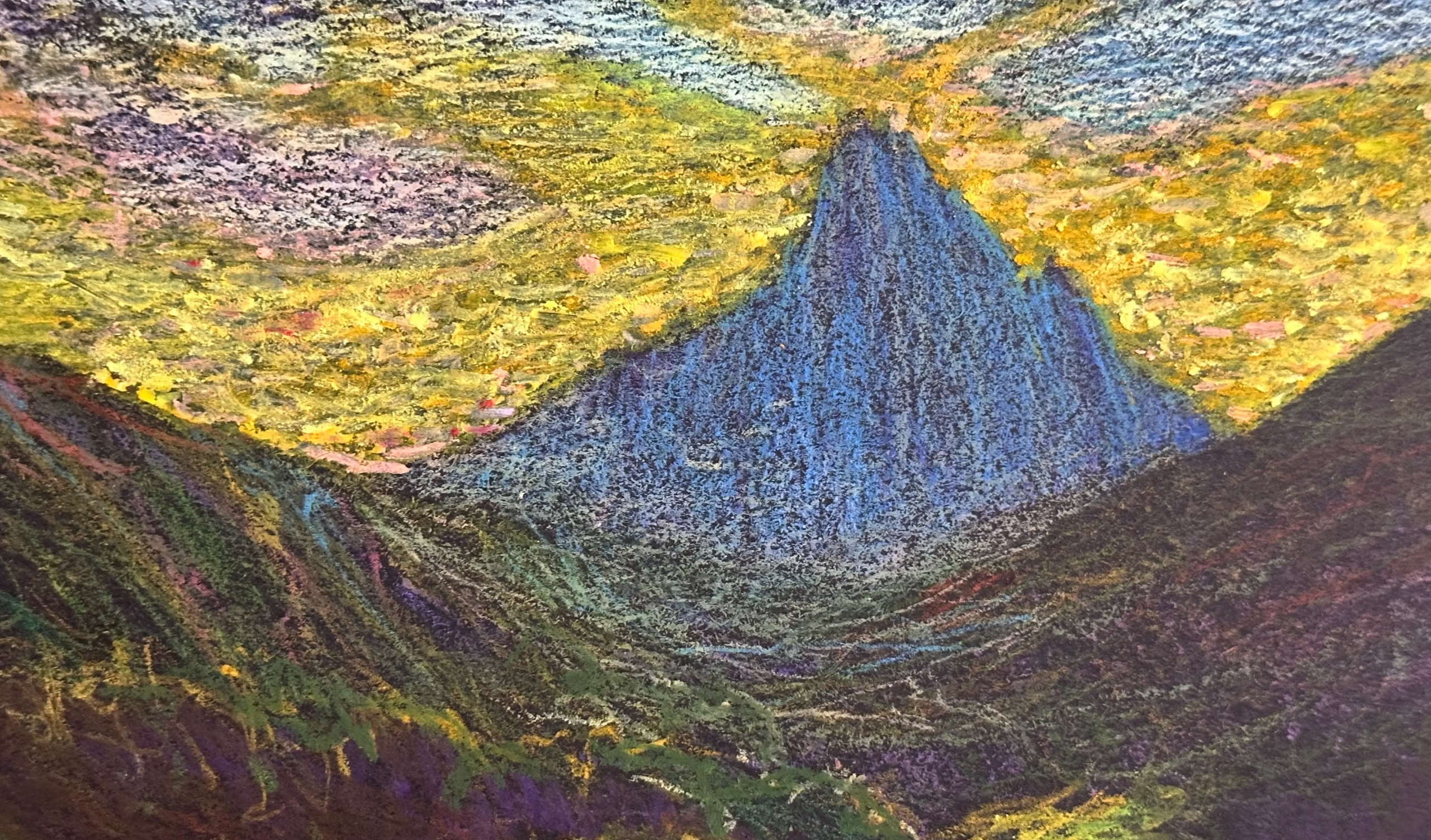

The valley is drawn as broad structure rather than detail: long green slopes fall away behind him, a dark ridge cuts across the middle distance, and a single blue peak rises under a sky scraped with yellow. Light is everywhere, but it’s not smooth. The black paper shows through in places, keeping the scene from becoming pastoral wallpaper.

The figure’s surface is built from layered color more than modeled anatomy. Reds and violets dominate the torso and limbs, with pale white lines and highlights catching the edges of shoulders, arms, and hair. That palette makes the body feel worked—heated by sun, stained by effort, or simply pressed into visibility. The face is present but not polished; features are rubbed in and partially lost, which keeps the gaze from becoming a portrait encounter and turns it into a posture: a person standing their ground.

The flowers at the bottom do not sit politely as “decoration.” They surge upward from the dark in yellows, magentas, reds, and purples, with quick, scratchy petals that feel improvised and alive. They function as foreground and as counterweight: their brightness pulls the eye down, then the figure’s gaze pulls it back up. The title, Night Gardener, lands here—not as a story, but as a role. The figure feels like someone who belongs to this hour, tending color where it shouldn’t be able to survive.